When a Lancaster woman was hit by a truck in 2016, the top neurosurgeon at Gates Vascular Institute was called to treat serious injuries to her head and neck. Dr. Elad Levy was confident he could perform the procedures that would help her overcome the injuries. But he wasn’t sure he could lay out the steps he took when it came time to explain them to a jury.

“The anatomy and the injuries were so complex that I didn’t feel I could adequately explain them,” he said.

It turned out he didn’t have to. A Buffalo personal injury law firm landed a $3.5 million legal settlement on the eve of the trial last month using a new form of evidence created on the Buffalo Niagara Medical Campus: colorized 3D models made with the plaintiff’s black- and-white imaging scans that showed damage caused in the crash.

“Lawyers have spent years trying to explain these types of injuries to jurors while a doctor is pointing to different shades of gray on an MRI or X-ray film 20 feet from the jury,” said attorney John J. Fromen Jr., who represented the injured woman.

“Some jurors get it. Some don’t. For jurors to hold a model that shows the injuries, take it with them to deliberate, is a real game changer.” Lawyers and doctors involved with the civil lawsuit believe it may be the first time personal, anatomically correct, three-dimensional medical models were used in a U.S. personal injury case.

Fromen and his partner, Frederick G. Attea, said it won’t be the last. They predict attorneys who bring these kinds of cases, and defend lawsuits, will clamor for such persuasive evidence as 3D modeling improves and its costs come down.

Meanwhile, advances on the Medical Campus that put the University at Buffalo and Gates Vascular Institute along the forefront of neurosurgery and medical technology allowed doctors and lawyers to help the injured victim address and compensate for her injuries.

The crash

On a midmorning in March 2016, a commercial truck driver traveling about 55 mph on a rain-slicked, 40 mph zone in Lancaster lost control of his vehicle, which skidded over a curb and grass median, and struck a part-time bookkeeper as she retrieved the mail for a family business.

The passenger side mirror of the truck slammed into the woman’s head. A metal running board below the passenger side door tore open her right leg. Fromen and Attea described the crash and aftermath on condition that the woman, truck driver and company not be named, a condition of the legal settlement.

The woman, now 58, spent a week in intensive care at Erie County Medical Center, and 23 days in the hospital after the crash, as doctors stabilized her injuries and repaired fractures in her leg. Scans conducted on the woman’s head and neck also showed aneurysms behind both her eyes and damage to several discs in her cervical spine.

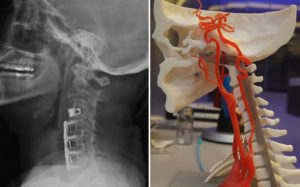

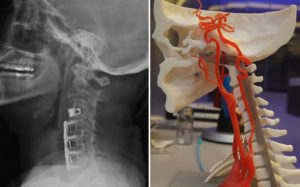

Levy – chair of the Department of Neurosurgery in the University at Buffalo Jacobs School of Medicine and Biomedical Sciences, and director of neuroendovascular services at Gates Vascular Institute – was assigned to deal with the head and neck injuries because of their complexity. In the following months, he used a catheter to insert springlike stents into her carotid arteries to bypass, and eventually dry up, the aneurysms. In two neck surgeries, Levy removed three spinal discs damaged during the crash, and used screws and metal cages to fuse four adjoining vertebrae in the upper spinal column. This limited the woman’s range of motion. She also continues to struggle with cognitive issues that include focus, memory and multitasking, her lawyers said.

The Strategy

John J. Fromen Jr. Attorneys at Law filed a lawsuit against the truck driver and his employer as the extent of their client’s injuries became clear. Months dragged on and a settlement couldn’t be reached, so Fromen and Attea lined up doctors who treated the woman, and prepared for trial. As the April 24 State Supreme Court trial date approached, the lawyers met with Levy to better understand their client’s injuries and go over potential testimony. Gates Vascular is a world-renowned stroke, spine and cardiac center. Levy and fellow surgeons use a $500,000 UB surgical simulator there to practice and teach procedures.

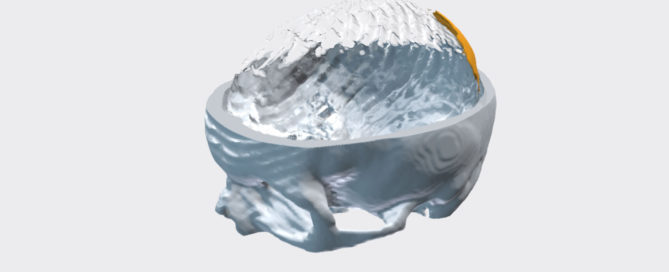

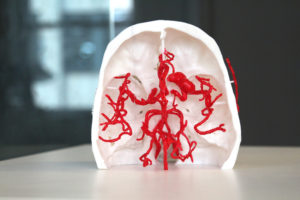

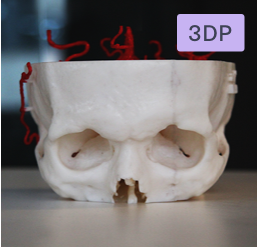

A 3D printing lab at the institute can produce replicas of organs, regulatory systems and other body parts using X-rays and other radiological images of patients about to undergo surgery. The malleable models feel rubbery, real. They replicate all the nooks and crannies of an individual patient’s anatomy. Specialists scheduled to operate can use the simulator and models to get a feel for potential trouble spots; say an unusual bend, bulge or narrowing in an artery, or a lesion inside an organ.

“We figure out where the hurdles are in the model first,” Levy said, “and it’s usually smooth sailing with the patient.”

The 3D lab contains two printers. The most sophisticated, a Stratasys Ltd. 3D printer-maker, can produce objects in color. “At the GVI, we do training for physicians and medical device manufacturers all over the world using this technology,” said Levy, also president of the UB neurosurgery physicians’ group. “Now, potentially, we could use similar technology to educate laypeople.”

The attorneys jumped at the chance for Gates Vascular and UB to test the idea that two models of their client could be turned into evidence for their court case. Normally in substantial personal injury cases that appear headed for trial, lawyers pay medical illustrators up to $10,000 to gather patient records and images, interview treating physicians and create one-dimensional drawings that show specific injuries. Generic body part models often are used for comparison. Attorneys then use black-and-white X-rays, MRIs and CT scans, as well as written medical reports, to bolster their case, said Fromen, a 32-year legal veteran.

Attea called the new approach “the CSI effect.”

Focus groups

Fromen and Attea wanted to show the models to focus groups to see how jurors might respond. One model depicted injuries to the arterial system inside the neck and skull. The second showed damage to the upper spinal column, where a ligament was torn from the spinal column, damaging several discs. The first models were produced in an off-white shade, which at times confused

some of the first of seven focus groups to see them. Using input from those groups, UB mechanical engineers produced colored models in which key body components better stood out. Spinal vertebrae remained white. Spinal discs, normally yellowish, were turned blue. A splash of red showed blood in the spinal column caused when the ligament tore loose.

The model of the arterial system was produced in pale red. Two small aneurysms behind the eyes remained white. The one Levy discovered behind the left eye was larger than the one behind the right. Had he been called to testify, he would have explained that they would have been the same size had they formed congenitally before the crash, and that a traumatic collision best accounted for them.

“Prior to this, we never had the ability to show jurors what an aneurysm looks like,” Fromen said. “This is my client’s actual anatomy down to thousands of sub-millimeters.”

Another idea resulted in cutting the rectangular model of the spinal column in half and adding a hinge, so injuries could be seen from the inside. “The doctor can get off the witness stand,” Fromen said, “show the model to the jury and say, ‘This is her spinal cord, and these are the damaged discs impinging on the spinal cord. That’s dangerous, because it could result in paralysis.’ It’s amazing how small someone’s spinal cord actually is and how the external and internal carotid arteries go to the neck and supply blood into the brain, and you can see it in these models.”

The future

Fromen and Attea settled the case for $3.5 million during a mediation conference on the eve of trial. It was the first time the defendant’s attorney and a representative from the insurance company involved in the case saw the 3D models. The computer-generated replicas, and the prospect that a leading surgeon would testify that injuries depicted were caused by the truck- pedestrian crash, were key to the settlement, lawyers for the plaintiff said.

The Lancaster crash victim and her husband, an engineer, were fascinated with the models and grateful they helped reach an acceptable settlement. Still, their lawyers said, it would have been better for them had a stranger made better choices while driving a slippery road three years ago.

“My client used to walk a lot,” Fromen said. “Now she can’t walk for extended periods of time or on uneven surfaces for a couple reasons. Number one is because the problems she has with her right leg, but her biggest fear is falling. If she falls, she’s got plates and screws in her neck. She could be paralyzed.”

Her experience after the crash may help others in the future who befall a similar fate, her lawyers said. UB and Gates can now produce the 3D models economically, Levy said, “but if somebody wanted to create these models for use in a court case, and turn it into a business, 3D printers are pretty expensive.”

Tags

Fromen and Attea believe someone will make such an investment, and likely become the go-to company to bolster medical-related legal cases. In fact, opportunities like this were what UB planners hoped for in 2012, when the university opened the Clinical and Translational Research Center on the floors above the Gates Vascular Institute.

Up next: Discover the differences between 2D images and 3D printing in the courtroom